The UK has seen a prevalence of unregulated investment schemes since the pension freedoms were introduced in 2015. Low interest rates have supposedly guaranteed return on investments deemed easy to sell, and unregulated sales agents have been charging up to 15% commission to sell seemingly secure investments in property. The reality is that many of these schemes have several of the hallmarks of a Ponzi scheme. While the FCA does not have a definition for a Ponzi scheme, the U.S. SEC does, and it is as follows:

“A Ponzi scheme is an investment fraud that involves the payment of purported returns to existing investors from funds contributed by new investors. Ponzi scheme organizers often solicit new investors by promising to invest funds in opportunities claimed to generate high returns with little or no risk. In many Ponzi schemes, the fraudsters focus on attracting new money to make promised payments to earlier-stage investors to create the false appearance that investors are profiting from a legitimate business.”

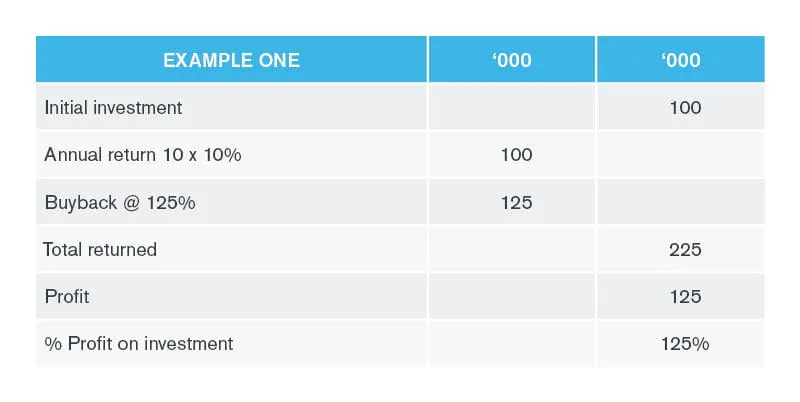

The schemes are often sold as investments in property, where the investor buys a long lease over such things as a room in a hotel/care home or a parking space in a carpark, but it could be anything that can be divided up into distinct parts—let’s call this “the Property.” The investor then leases back the Property to an operating company owned and controlled by the owner of the hotel/care home/carpark (“the Owner”) on a shorter lease—typically 10 years—in return for a “guaranteed” return. Typical returns are 10%. In most schemes, there is a buyback clause where the Owner will buyback the long lease at typically 125% of the original purchase price. So, the schemes purport to give you a profit of 125% [10 x 10% annual return plus 25% profit on buyback] over 10 years.

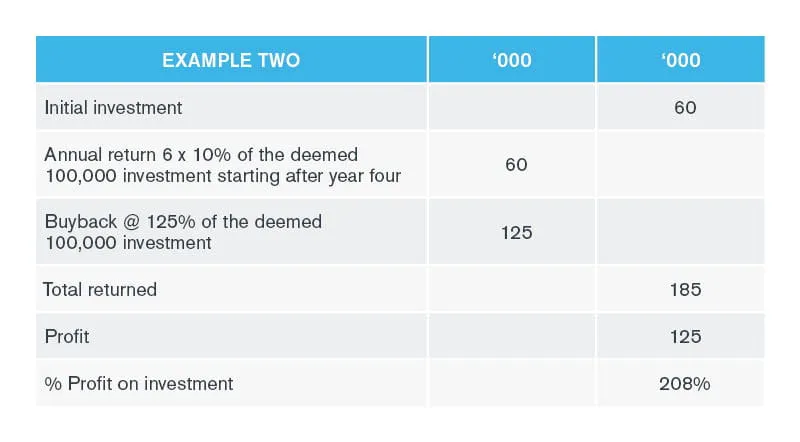

Now, in these times of low interest rates, the ability to get such a high return by handing over your funds to somebody else must raise some alarm bells. In addition, incentives were often included to reduce the initial investment and defer returns, which as the example below shows, resulted in an even greater percentage return.

Often the buy-in price was 100,000 so the return was as follows:

However, under a deferred model the buy-in price would be as follows:

If you consider commissions of 15% charged by some agents on the deemed investment model, then in the deferred model the scheme would have had to generate a return of c. 280% over 10 years to meet the investment model.

You may wonder why these schemes are not regulated. Certain lawyers acting for many of the schemes have argued to the FCA that the investments were interests in property marketed to high-net-worth individuals, and therefore, not subject to regulation. In reality, many of these schemes were marketed in a boiler-room type operation with high-pressure tactics to ordinary retail investors, who had cashed in pensions or remortgaged their parents’ houses (often to fund care home bills).

Investors were also sold the schemes on a ringfenced basis by the sales agents, although in many cases the documentation did not mirror the representations, and the funds received by the Owners were used to fund a lifestyle, pay returns to earlier investors and manage losses in the various operating businesses. Ultimately, the key driver for the Owners was to buy more properties to sell rather than to successfully trade the hotel/care home/carpark.

At some point, the requirement to meet returns to investors cannot be met by the ability of the Owners to buy more properties and raise further investment, and the schemes collapse. The fallout is complicated and the situation arises where competing claims surface over the assets, as often, the Owners have borrowed money from financial institutions secured on either the whole or elements of the properties; for example, the investor owns the rooms, but the corridors are owned by the financial institution. The Insolvency Act 1986 has not historically offered a solution due to the proprietary interests of various creditors; however, the recent COVID-19-related additions to the Insolvency Act may offer a way forward, although this will need the help of the courts, which will undoubtedly be costly and reduce any return to investors. The major asset in the schemes may be the claims against lawyers, as the Solicitors Regulation Authority had issued several warning notices to law firms regarding acting for Owners.